“The ghosts live in four wood houses, each one deeper than the preceding one”.* Mossy are their roofs, crowded their walls that gleam in the dark. From blackthorn are the logs of the houses ‘gates that are kept shut until the bell has rung. The ghosts dwell where the fire crackles if you taste their food, you will be trapped.

Old lament from origin unknown.

During the XVIII century, both in North America and in Europe, there was a relentless sickness that killed more people than any war had before: Tuberculosis. Back then the illness took on as many names as victims. Some called it consumption, due to the extreme weight loss of the sufferers which appeared to be rapidly consumed by the infection. Others called it the white plague because of the severe paleness of the sick. Children and young adults were among the first casualties of the white death who robbed countless generations of their youth.

Even though Tuberculosis is an old disease, a hundred-fifty-million years kinda old, it became the most virulent during the beginning of the 18th century where it plagued without mercy and prayed on half the population. Entire towns emptied little by little and became abandoned.

This story talks about a town such as this where a young couple of farmers was expecting their first child. The parents were thrilled with the news of life in a time of constant mourning. And, during nine months and some days, they built bit by bit a tree house at the top of an old Cedar tree in the woods nearby. What began being just a playground for their children (they had three more daughters to come) ended up being a refuge from the white plague. The family spent more and more time in the heights than in the ground, but the parents still had to go back to town every day to take care of their small farm. When the last of four daughters was born, the father contracted Tuberculosis and died in a matter of weeks.

After the funeral, the mother took the four little girls back to the cedar tree and confined them in the safe heights of the tree house. They spent their childhoods among branches and birds’ nests, never touching the ground again.

They relied on their mother to bring them food and clean clothes every day at sunrise. And every day the mother climbed the wood steps of the tree house carrying a basket full with the news of the day and, on special occasions, a smoking sweet potato pie.

Photo by Luís Perdigão on Unsplash

She rang the bell at the doorstep and the five of them sat then on the thickest branch gazing beyond the canopy of the forest, towards the rising sun. The mother told them, again, about the time she and their father had built the tree house with the wish that their daughters would learn the early songs of the blackbirds and the lullabies of the nightingales. Perhaps in time, they would suddenly take off and fly.

Photo by Filip Zrnzević on Unsplash

But none of them had learned how to fly and so they all remained in the crooked tree house, taking turns at the tilted old swing; rocking back and forth in breezy summer afternoons.

The older they grew, the more time they spent swaying in the swing, hoping if they pushed one another hard enough, it would take them somewhere new, a piece of the world yet unseen from their treetop. But no matter how windy a day was, the wind was never strong enough to let them overlook anything else but their old forest with its familiar colours and shapes.

Photo by Daniel J. Schwarz on Unsplash

That was the world they knew best, despite the anecdotes and gossip that their mother brought from the town. Almost half of it had been wiped out due to the cold muddy winters and the mosquito-infested sweaty summers. Not her daughters, though, they grew untouched by the fatal sickness. Hardy and strong like cedar bark.

Consumption had been raging for decades now. Even family members who were seemingly healthy would fall sick after years without a symptom and die, leaving a trail of bloody spit on the peach coloured wallpapers of their rooms. A decor of death that told the screaming story of shock and suffering.

But not her daughters. While the town was turning black – black were its inhabitants’ robes, black were their coffins- her daughters were fair and light. Their songs, bright as the burning sky is on top of a peak, contrasted the mournful sounds of grieving from the decaying town.

Life continued uninterrupted on the slow lane but, as years passed by, it became harder and harder for the mother to climb the wood steps of the tree house. The oldest was shy from seventeen then and the youngest barely eleven. One morning, a morning no different than any other, the mother did not come up. They saw her from far away, down at the base of the tree, resting and trying to catch her breath. A basket full of news and a smoking sweet potato pie was left unattended next to the cedar trunk and mice and ants were furtively robbing the family meal. The sisters were never taught how to climb down and, after so many stories about the plague, they thought their mother was about to die.

It was the youngest of the four who, quickly, ran to the swing thinking that was the easiest way down to help her mother. She rocked herself way past the edge of the longest branch and then, just like that, she jumped.

The mother froze in horror when she felt, before she saw, the earth shake with the impact of her young daughter´s body. Then she heard the sound of her hardy bones breaking at once and how her last breath, mixed with blood, bubbled outside her lifeless child. That was the first time she ever touched the ground.

Two more sisters soon followed. One perched herself from a branch just like an owl, upside down she saw the world below for the last time. Perhaps this one had learned the secret of flight. She loosened her foot and let go of the branch. For a moment it seemed she was suspended in the air. But just for a moment because, rapidly, gravity grabbed her with a heavy hand and crashed her down.

The third of the sisters, stroke by sadness, grabbed the garnetted rope that held the swing together, rolled it around her neck and took a step into the void. That snapping sound of her neck made all the remaining birds in the forest fly away. She never touched the ground.

Only one sister was left in the house at the top of the cedar tree, the oldest, shy of seventeen. The mother screamed for her not to leave the house. But it was too late, she had seen it all. All her sisters now mapping the forest. One hanging on a branch like a beautiful pendant. One with her face down the ground almost buried like a seed in the soil. And the smallest one, the sweetest one, who had thought she was a bird, laying broken in her old mother’s arms.

That night, unlike any other night, the forest was utterly silent.

Only the slow steps of the mother climbing up the tree could be heard. It took her almost all night but she finally reached the last step and the house. There was no laughter, as there used to be, no melodies, no sounds. Her remaining daughter, the oldest one, laid alone in the canopy world, below a starless night. As still as stone, cold as ice. In her hand, the bell of the house that so many times welcomed her mother was tightly clutched.

With the first light, she sat her daughter in the empty basket and carefully brought her down the tree house. She walked to town with her heart sunken and paid the priest for five funerals services. For her four daughters and her own, because she had coughed the first blood that morning and knew to be dying of consumption at last. As it was, not half a day had passed that she was laying as still as her daughters in their black winter dresses.

Not many people came to the funerals, then again not many people lived in town any more. Most lived in isolation for fear of contracting the disease. But every tree in the graveyard was full of all kinds of birds that were arriving from every corner of the forest. Their world was there, singing the farewell song of nightingales.

The five coffins were buried underground, each one a bit deeper than the other; resembling the staircase of the tree house. The mother was buried close to her late husband, who had died eleven years before. And the seventeen-year-old daughter still had in her hand the doorbell just as she did when she awaited that last night for her mother in the old cedar house.

Night fell quickly. The nocturnal birds were hatching in the graveyard trees when the oldest sister woke up all of a sudden. Unsure if she was alive or dead, or perhaps in the border between those two states, she screamed like two hundred tonnes of earth were crashing her lungs, she screamed like a whole colony of flesh-eating maggots were creeping every fold of her skin. But the ground swallowed her cry. She punched and kicked the coffin, but the ground surrounded it and kept it earthward. Outside, the night was quietly disturbed only by the wind softly ruffling the leaves of the oak trees. But inside, inside there was a human being, in absolute terror, coming to the mind-breaking realization that she had been buried alive.

At that moment she noticed the familiar cold touch of the bell in her palm. She shook it, and again. And the bell ring resonated in the coffin, like metal on a crystal glass. A deafening high pitch ring that pierced through soil and stones all down to the earth, awakening whatever creatures laid dormant there.

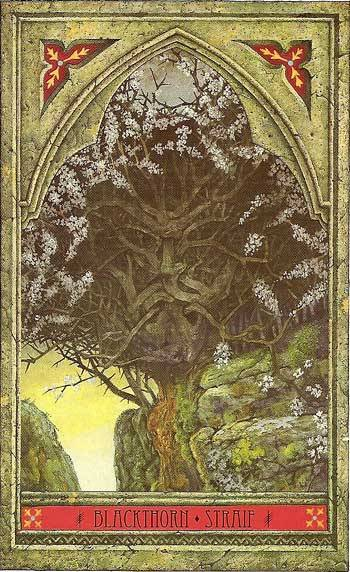

The Green Man Tree Oracle by John Matthews & Will Worthington

The ghosts live in four wood houses, each one deeper than the preceding one. Mossy are their roofs, crowded their walls that gleam in the dark. From blackthorn are the logs of the houses ‘gates that are kept shut until the bell has rung. The ghosts dwell where the fire crackles if you taste their food, you will be trapped.

The first house was still humming the old tune of the bell when she entered a dim hallway whose walls were softly lit by the crackling fire nearby. Ivies had taken over the surface and the roof, falling graciously like stalactites in a cave. She made way, carefully brushing them to the side, and found herself in what appeared to be a tiny cabin with a great fireplace on the ceiling. Right below it an old woman was sitting on a swing that was hanging from the ceiling above. She was slowly knitting a small patched quilt. The elderly lady looked just like her mother; the same curious eyes wandered the textures of the blanket in her lap, the same calm smile was peeking from her hood. And yet, something about her was alien.

She sat by her, on the swing, and they rocked together for a moment. She noticed every patch of the quilt was a little fragment of a story. There were blackbirds and owls, there were pies and tall trees with thick branches and leafs changing as seasons do. She was reading that story while knitting it like a blind person can read the contours of things and faces by their touch.

Photo by Nathan Anderson on Unsplash

The old lady paused for a moment, catching her breath, and a thin brook of blood was going down her chin. She did not seem to mind it, instead, she offered her a spoon and presented her with a splendid sweet potato pie. But before she could even smell the splendid pie a voice called her from the outside. She stepped out, leaving the old lady snoozing on the rocking swing.

Strangely, as soon as she exited the cabin she entered another house. She knocked on wood – as one does when first arriving- and realized the new house looked just like the previous one, only darker. The Ivy was crawling all over the walls, lit by the great fireplace on the ceiling. The swing was rocking softly and the old lady was knitting the quilt. The brook of blood in her chin had become a small stream and was running all over the blanket creating, in turn, new pathways in the fabric.

Besides the fact the quilt was a bit bloody now, it had changed in other ways as well. It was larger, new patches had been added revealing a new part of the story. She could see the new fragments were showing the life in town and were, contrary to the forest patches, somewhat hollow with only gray silhouettes against black. She could discern dark crosses in dirty peach coloured rooms. And eyes, so many eyes rolling and staring back.

The back of the old woman was much more crooked than it had been, she was bent and twisted awkwardly but still smiling. She offered her the spoon, she told her about the splendid pie and as soon as she did, a voice called her from the outside.

As if she had been summoned, she found herself in another wooden house. The air felt stalled and rancid. There was barely any space to move due to the completely overgrown ivies. It was not a hallway any more, it was a thick humid forest containing just enough light to glimpse the great fireplace on the ceiling. The old woman was not sitting any more, she was perched on the swing hanging high from the ceiling, like a bird on a branch. Humpback and terribly bloody. The quilt was spread all over the floor. Blood running through it like a viscous ocean. Before she could smell the pie, before she could check the new patching fragments; the old lady jumped from the heights of the swing. Her neck, strangled by an invisible force, cracked in unison with the bursting wood in the great fireplace.

She was smiling.

The old woman was hanging, suspended in the air, with a twisted neck and a waterfall of blood pouring from her chin. She opened her mouth and called for her daughter. But, despite the fact that her lips were moving, her voice actually came from the outside of the house.

She was standing in the fourth house of the ghosts. Deeper than any other before. She had the feeling she had been descending an underground world, layer by layer, step by step, until the hallway of a dungeon. So gloomy it was that she could only catch sight of the blazing embers in the great fireplace on the ceiling. As she got closer, the entire chamber grew to cathedral proportions and was thoroughly lined with the patched quilt. The blood had dried off and tinged every scene with a beautiful crimson.

She circled the room and saw the grand narrative the old lady had been knitting. The figures of the quilt were popping in and out of the lining playfully. Nightingales were hovering over her, catching fire only to return to the safe nest of their plot on the wall’s lining. The town folk, who had died of consumption long ago, crowded and chatted carefree. While their eyes, with a mind of their own, were popping out of their patches to chase after some scared owls. Her sisters took off from the quilt and flew over a familiar cedar tree.

The mother, though, was still swaying on the old swing, finishing the last touches in the blanket. By her, sat her father with the sweet potato pie. It smelled so delicious that it made her mouth water so she went for a bite.

But as she approached, she saw the final fragment in the quilt. And it was herself, laying on a bed made of cedar wood. In her hair, a twig of lady mantel, in her hand, the doorbell of her home. She felt the warm familiar touch in her palm and she rang it once more.

They say they found the last of four sisters in a deep sleep covered with a thick crimson quilt. She had suffered what was not uncommon back then, a premature burial. But the blanket had kept her warm enough to survive the night underground. She remained unconscious for a time like someone who does not wish to leave a nice dream behind. But she did wake, and the very first thing she did was to touch the ground.

*Literal quote from Walking with spirits Volume 3. Native American myths, legends and folklore by G.W. Mullins and C.L. Hause. This story is an adaptation of The ghost country legend. No copyright infringement is intended.